Mystery of the Wax Museum, Restored: Q&A with Scott MacQueen

Jennifer Rhee 04/21/2020

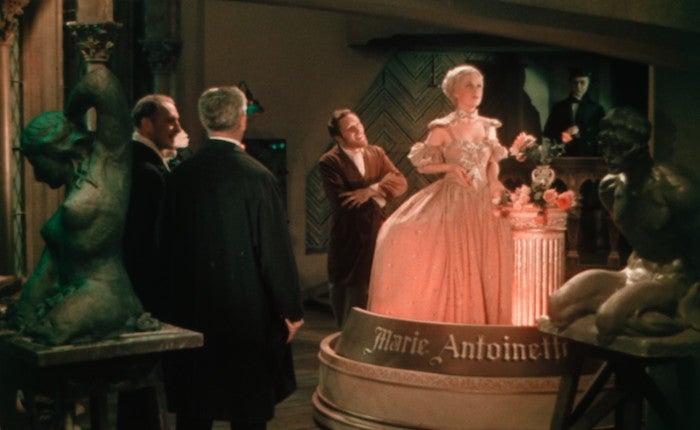

Lionel Atwill in Mystery of the Wax Museum

Released at the tail end of the 1930s horror craze, Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) delivered chills with its macabre plot (thought “too ghastly for comfort” and “unhealthy” by one New York Times critic) and effective use of the surreal two-color Technicolor palette, which was soon phased out for the more realistic three-color process. The Warner Bros. film reunited legendary director Michael Curtiz with his Doctor X (1932) cinematographer Ray Rennahan, a master in the art and technique of early color film, and actors Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray. Now a classic, Wax Museum was believed to be lost for decades until an original nitrate print was located in the collection of studio mogul Jack Warner. In 2019, the UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation undertook a new restoration with funding from the George Lucas Family Foundation, combining and repairing the best surviving 35mm elements. This restored version will be released on Blu-ray/DVD by the Warner Archive Collection in May.

In this interview, the Archive's Head of Preservation Scott MacQueen discusses the film's production history and recent restoration. He also provides in-depth audio commentary as a bonus feature on the Blu-ray/DVD.

What’s your personal connection to this movie?

It’s a film that’s fascinated me since I was a youngster. I had seen the remake House of Wax (1953) on late-night TV so I knew the story and thought, “There’s an earlier version? And it was in color in the 1930s? And the girl from King Kong is in it? Wow, I want to see this.” And then I heard it was lost. So it was always in the back of my mind, as it was for many of my generation who started to embrace old movies growing up. I got a paper route in the late-'60s on my little country road in New York and actress Glenda Farrell was one of my customers. I knew her only as Mrs. Ross, “The Movie Star Who Lived Up the Road.” I began doing film research and discovered that she was in Wax Museum, so I cold-called her one morning and she gave me a phone interview. I was an old man of 13.

Glenda Farrell

What were the source materials for this restoration?

We used a 1933 nitrate print that was discovered around 1969 in Jack Warner’s vault at Warner Bros. A second nitrate copy was found in the 2000s by a collector and is now in the Packard Humanities Institute collection. It’s a French work print of some kind for subtitling—some reels with English sound, some reels with no sound, most reels with French subtitles. There were places where it was undamaged and had additional frames compared to the Jack Warner print. We probably picked up half a dozen shots from it, though it had inferior color. We were able to electronically grade it to match the Warner print. We were also able to get lost frames back, including a line of Glenda Farrell’s: “I asked you to keep your trap shut!” The Warner print has a splice there. We had to borrow Miss Farrell’s words from her 1932 movie Life Begins to fill in the missing dialogue.

French work print used in the restoration

What was the restoration process?

The two nitrate prints were scanned at 4K resolution at Warner Bros. Motion Picture Imaging. We partnered with Roundabout Entertainment on the picture clean-up and grading; they digitally cleaned the damage and made major repairs and full color correction, as dye transfer prints frequently don’t match across reels. It was clear that the Jack Warner print had been cobbled together from a variety of prints with different color balances. The restored color is more consistent than the original print. We worked with Audio Mechanics to restore the sound, removing any noise and adding the missing words. It has a clarity now we’ve never experienced, quiet without sounding processed. Subtleties that have been forever masked, like the heavy breathing of the morgue monster, are heard for the first time. We now hear the subtle sound of a museum employee slipping a dagger into the chest of the wax figure of Marat. These sounds would have been barely audible in 1933, when a typical theatrical speaker reproduced little higher than 8000 Hertz. Even an obvious effect, like the sudden twang of a barrel organ being set in an exhibit, is so clear and dynamic that it finally achieves its original purpose of making the audience jump.

Before and after the restoration

What was two-color Technicolor film in the early 1930s and what happens to it over time?

Technicolor patented a camera that allowed two exposures to be shot on one piece of film through a prism that split the light through two apertures and used two filters—red and green. From one negative they optically separated the frames into two “matrix” positive films, inked them up, one red and one green, and transferred the dyes onto a blank film that had the soundtrack pre-printed on it. They were like lithographic printing plates. They’re relatively stable dyes. The colors in the original 1933 nitrate print have held very well, for 90 almost years, because they are not organic dyes like Eastmancolor film.

How did Wax Museum cinematographer Ray Rennahan pioneer the use of color in film?

Rennahan was the first Technicolor cameraman. He was with the company from the very beginning in 1915 and worked exclusively with them into the 1930s. He did all their tests, was there all through the evolution of the process, and was probably the greatest cinematic color expert at the time. On Wax Museum he experimented heavily with what he called “projected color,” which is filtered color light. He used it to add an ominous green to the horror aspects, mixing it with white light on the principal actors so they could move through a spooky world, and red-orange for danger. In interviews, Rennahan said he was proudest of his work in Doctor X and Wax Museum. In 1970 when he saw the earliest attempt to restore Wax Museum with the basic tools of the day, he was so dismayed that he walked out of the theater. The art and craft of restoration has come a long way in 50 years. I think Rennahan would be proud of the way it looks now.

Is it true they used actors in place of wax figures because of the extremely hot lights?

That’s partly true. They also wanted some of the actors to really look like their wax counterparts. Variety reported a month before production that Warner Bros. was advertising for vaudeville performers who were good at holding poses, so it was clearly intended that some of the figures would be portrayed by humans. But there’s no question that statues did melt. In fact, there’s a story about Michael Curtiz shooting all through the night when a couple of wax figures began to fall over at 3 in the morning. The actors were also falling down. Curtiz finally sent everyone home when the drooping wax figures hit the floor. Both film stars Fay Wray and Glenda Farrell talked to me about that, it was just awful. He would keep on shooting, and then finally one of the wax heads would just fall off. He’d say, “That’s it, go home.”

Watch before-and-after clips of the restoration (please note there is no sound):

UCLA Film & Television Archive