Defogging Wanda

Ross Lipman 03/25/2019

In early 2007 the UCLA Film & Television Archive received a call from Hollywood Film and Video announcing that the lab was, sadly, closing—and clearing its vaults in two days’ time. Anything left was doomed to the dumpster. The next morning a group of us arrived to see what we could salvage.

Walking through the musty basement, dank stairwells, and narrow aisles was like walking through a shuffled deck of cards: artifacts from the 1950s to the present lay atop each other, in seemingly unknowable order. The only light came from a few incandescent bulbs hanging irregularly amid the dark corridors of shelves, casting a yellow glow that dropped quickly into shadow. Aging equipment was everywhere, some still functional, some showing years of rust, dust, and corrosion. Puddles of oily water lurked underfoot reflecting sickly rainbows, and the smell of old chemicals and mold hung in the air.

The films lay about in differing arrays, long forgotten by their makers: B, C, and D movies, industrial films, commercials, printing tests, and the stray experimental short. We began making piles to save in our collection.

In one aisle, buried in a large stack on the floor, I found some 16 mm reels labeled “WANDA. Harry Shuster.” Who on earth was he? Surely this couldn’t be the classic independent film by Barbara Loden? Her name was nowhere to be found on either the boxes or the leaders. Taking no chances, I kept the oddity apart from my other discoveries; in fact, I took it back to our lab in my own car.

Immediately unspooling the reels on my workbench upon arriving, I realized we’d uncovered a piece of history. It was that Wanda—and no less than its original camera rolls. Harry Shuster, as I’d guessed, was the film’s producer. One more day and it would have gone to landfill.

But how to fund a restoration? Enter The Film Foundation, which has saved so many classic works over the years. In coincidental great timing, they’d recently begun a partnership with Gucci, whose express aim was preserving works by women visionaries. And so our work commenced.

At that time digital restoration was advancing rapidly but had not yet overtaken photochemical printing in archival practice. Thus our work would be on good old-fashioned film, at least initially. We began as Loden had herself, with a blow-up to 35 mm. But our route quickly began to vary. The exact stocks she used no longer existed, and their “official” replacements were problematic, increasing contrast and distorting color.

A crucial component of Wanda’s production, as I found in the camera rolls, was its Kodak Ektachrome ECB (7242) film stock, which has a unique color palette completely unlike Eastmancolor negative, Eastman Commercial film (ECO), or Kodachrome. In a stroke of luck, the bulk of the film was on this, and unfaded.

After extensive testing at Cinetech Laboratory we decided to avoid Kodak’s designated internegative, a holdover from a previous era that was not optimized for printing from projection-contrast film. To reduce contrast, we instead printed the reversal camera rolls to a low-speed negative camera stock and used pull-processing to reduce contrast—as I’d successfully done on a number of past titles. It’s interesting to note that in the intervening years, Kodak abandoned the interneg I nixed in favor of the camera stock. But this was years before that took place, and the result was stunning color.

Ironically, this led to what might strike some as an archival quandary. While the new color closely matched the original rolls, it was in fact much better than the old distribution prints, which apparently looked awful. To quote an early review in the British journal Films and Filming by Gordon Gow:

For the first couple of minutes, I thought it was all a ghastly mistake, this terrible muzz-colour . . . But soon it became obvious that Barbara Loden meant it to look messy, as if real life had been recorded perchance by an amateur photographer with cheap film and poor laboratory facilities.

It’s a nice interpretation. But was it valid? In Film Journal’s Summer 1971 interview with Loden, I found this:

Ruby Melton: The color in the film often has a washed-out, grainy effect and the lighting is sometimes very dim. Were these effects intentional?

Barbara Loden: Unless you have your own laboratory, it's difficult to control the quality of the color. In our original print the color looked extremely good, but later prints made by different labs were not such good quality.

Another question that arose was aspect ratio. 1.85 was clearly written on the leaders of an old 1970 distribution print in UCLA’s collection, as was common with 35 mm features at the time. Yet others disagreed. A pre-restoration French DVD release by Isabelle Huppert, Ronald Chammah, and Gemini Films chose the 16 mm native aspect ratio of 1.33, while the U.S. pre-restoration Parlour Pictures DVD release chose 1.66, in dialogue with the film’s cinematographer, Nick Proferes.

To get to the bottom of the matter, I consulted Proferes directly. He told me that Wanda had been shot on a 16 mm Auricon hand-modified by none other than D. A. Pennebaker to a wider aspect ratio. In those days Super 16 was coming into popularity as a low-budget option that offered a wider aspect ratio, 1.66, when blown up to 35 mm for theatrical exhibition. Rather than re-outfit his company with Super 16 gear, Pennebaker literally hand-filed his camera’s aperture plates to something near 1.66 for the shooting of his concert film Sweet Toronto.

Yet I had the original camera rolls in my hands, and it was clearly 1.33, on double perf stock that would have precluded a 1.66 or Super-16 shoot. To be sure I wasn’t delusional I also checked with Pennebaker himself, who said quite certainly that Proferes hadn’t used one of his modified Auricons on Wanda. My guess is Nick used it on another, later film.

1/4

In this slideshow, one can compare 1.33 and 1.66 versions of the same shots. The 1.33:1 samples are scanned from the restoration blow-up internegative, and the 1.66:1 samples are from a prior DVD release, which was transferred from an old internegative. The samples illustrate how Wanda was shot safely for both aspect ratios. While the majority of the film has headroom suggesting widescreen intent, problematic moments arise. Note as well the qualitative difference between the sources. Both are only one printing generation away from the original 16 mm reversal camera rolls, but the restoration negative has substantially finer tonal detail. The old internegative also exhibits color pollution in its grain pattern.

The above shot is in 1.33:1—classical composition with Barbara Loden’s head vertically centered and fully depicted.

2/4

1.66:1—cropped. 1.66 framing was likely intended (and successful) due to the vertical frame level of Loden’s eyes and her position frame right, but the shot is less balanced than the 1.33.

3/4

1.33:1—Loden is fully framed within the shot.

4/4

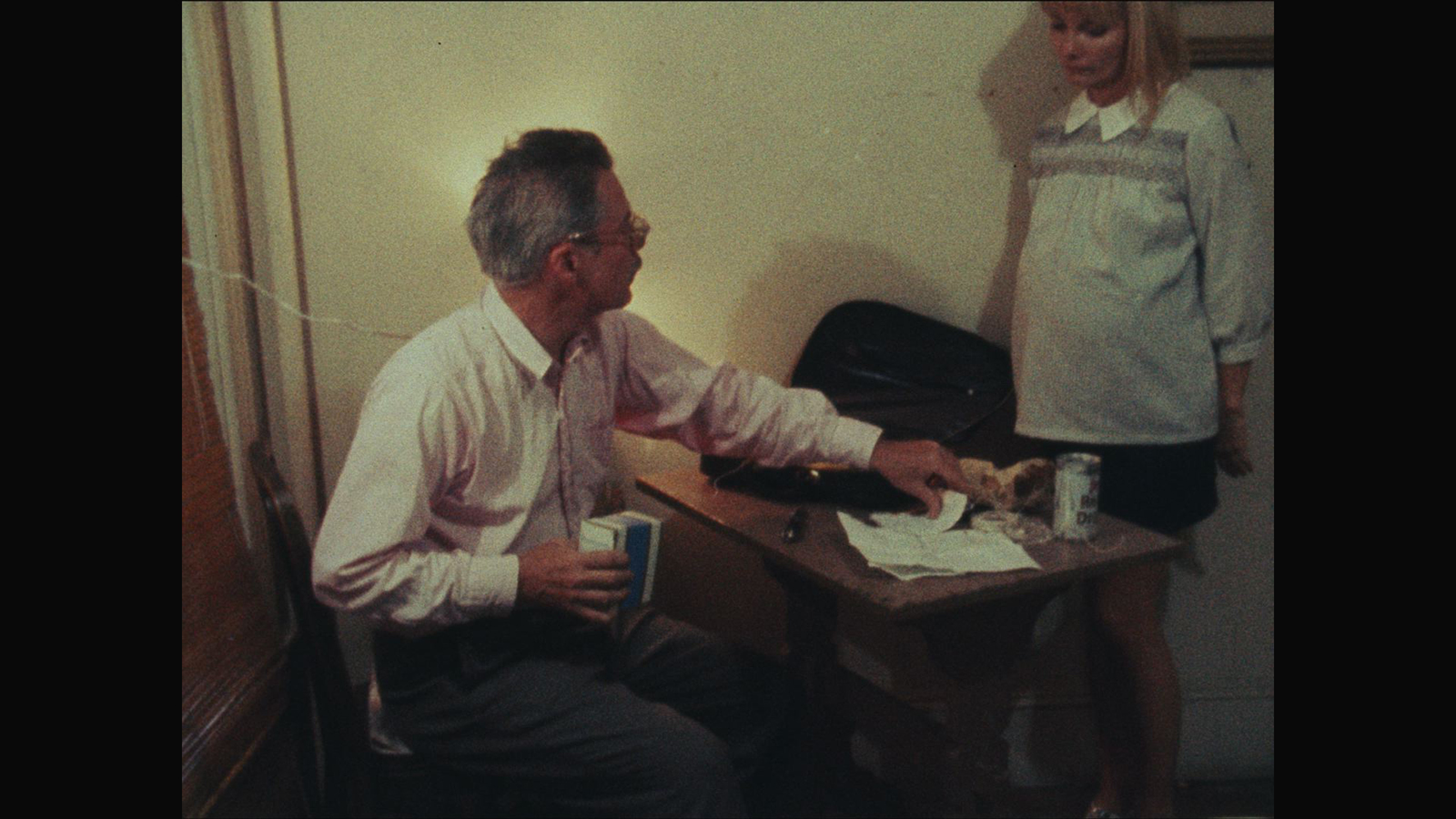

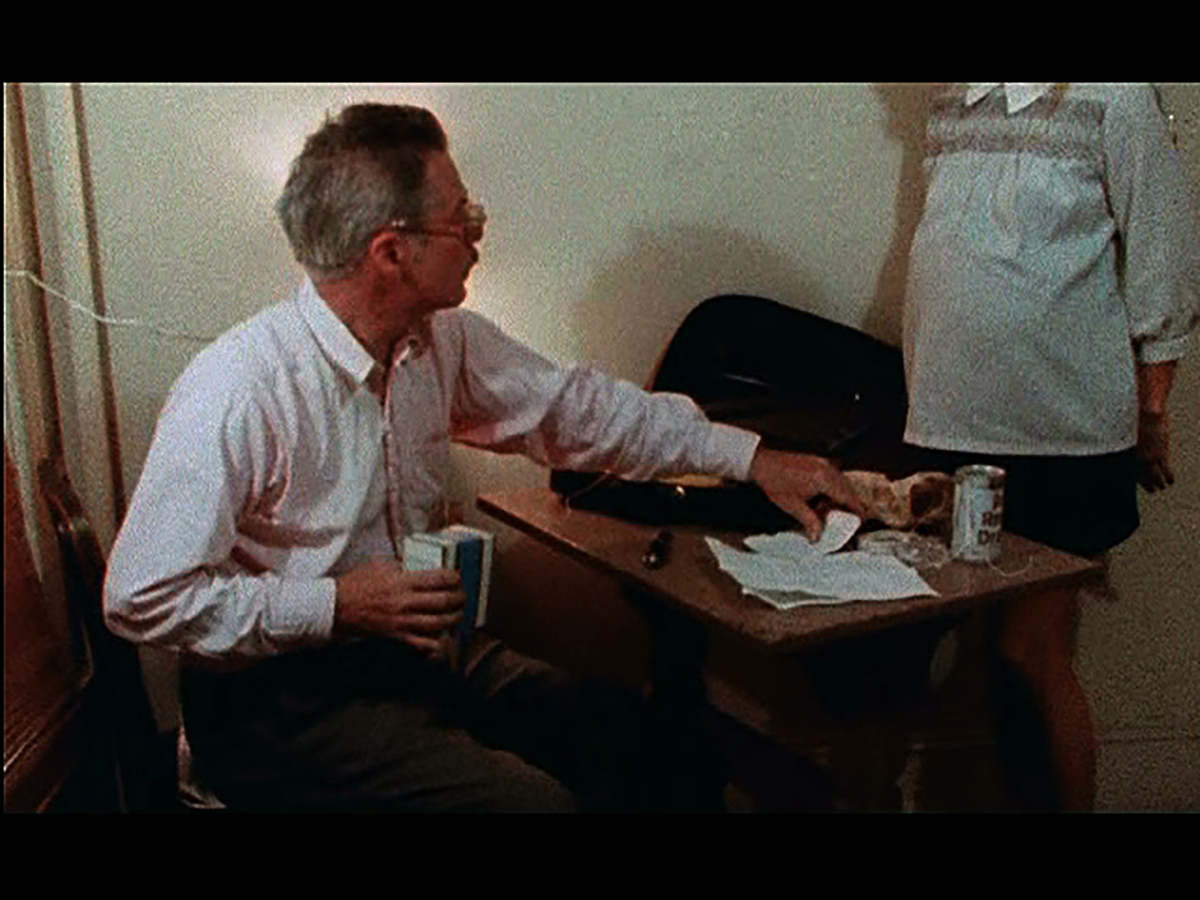

1.66:1—cropped, with Loden’s head cut off. This shot features extensive motion that the camera tracks, but due to the unpredictability of action, it occasionally loses track of important compositional details. It’s still successful at 1.66, as the pillow in Loden’s shirt and Michael Higgins are the intended points of emphasis, but the framing results in a slightly distracting awkwardness.

The question returns then: how should one frame it? In looking closely at Wanda, it became apparent that all ratios worked well. My ultimate assessment was that Profores shot Wanda with both Academy format and widescreen exhibition in mind, as was sometimes done at the time. But none of the ratios worked for the whole movie. Virtually all shots had plenty of headroom and are most pleasing at 1.66, suggesting widescreen intentions—but there were moments of exception where both 1.85 and 1.66 proved problematic. To do the highest quality widescreen release in either of those formats would have required numerous framing “repos,” or re-positionings—something Loden hadn’t done at the time. In its native 1.33, many shots had copious headroom, but also a kind of classicism, with no invasive boom mikes. Further, Nick told me he had no widescreen guides in his viewfinder, so the camera’s 1.33 frame was his only visible guide while shooting.

At the time of the restoration, our workflow itself dictated which ratio we would choose. The project mandated true archival preservation to 35 mm film, and to save all picture information. We thus opted for a 1.33 preservation negative to make sure nothing was lost. That method prohibited repos, so our “safe” recommended projection aspect ratio was the classic 1.37/Academy ratio. Projectionists and venues could of course opt to vary from that if they so chose, by simply changing their projector plates.

The restoration premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010. Nick was one of the guests and confirmed he thought the Academy ratio worked wonderfully. Our choice was in a sense validated years after the restoration was completed, when I came across an earlier interview with Nick. In the 1991 documentary I Am Wanda, he clearly states, “we had no idea of blowing it up.” Was this prior memory more accurate than his later one? It seems likely, but in the end the images tell their own story . . . and with so many conflicting accounts, I like to think the jury will always be out.

The MoMA screening was a huge success, with lines around the block, Sofia Coppola introducing, and—so I heard—Madonna incognito in the audience. Years later, we digitized the film for TCM at Modern VideoFilm with ace colorist Gregg Garvin, and I was delighted when Criterion picked it up for distribution in 2018.

Nowadays it’s common to digitize but rarer to complete photochemical stages of restoration. Wanda’s restoration journey was hence fortunate to encompass both analog and digital editions. The current release retains the Academy aspect ratio and color grading, but has, happily, applied further digital cleanup, eliminating excess dirt and scratches we’d been unable to address in our earlier work.

Today the film looks better than ever. It belies the oversimplified maxim that a restoration must look like the old viewing prints rather than its source, a notion that holds better for Hollywood titles than independent works. The film is now recognized as an American classic. Tracing Wanda’s trajectory, from its original release in shoddy prints, to the 2010 35 mm restoration that brought it back, to the Criterion digital release today, is to see a lost masterpiece arise from a fog.

All images courtesy of Marco Joachim, UCLA Film and Television Archive, and The Film Foundation/Gucci.

Inside Criterion