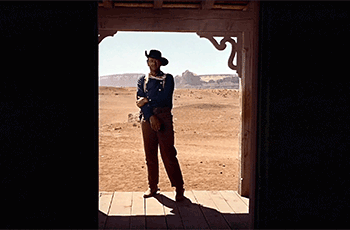

Maximilian Schell, Peter Ustinov, Jess Hahn, Melina Mercouri, Robert Morley, and Gilles Ségal in Topkapi (1964)

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

News

Martin Scorsese on the importance of film restoration

Ben Tracy

Martin Scorsese's meticulous and unsparing approach to filmmaking has made him one of the most acclaimed directors of all time. And in his New York screening room, it was quite clear that he's not just passionate about moviemaking, but also movie caretaking.

He showed correspondent Ben Tracy before-and-after scenes from a restored version of 1955's "East of Eden," starring James Dean. "Now it suddenly comes to life," Scorsese said. "The actors come to life when their faces can be really perceived properly."

"It's like having a cataract removed!" Tracy said.

This is just one of the more than 950 films restored with the support of the Film Foundation, which has been essential to preserving cinematic history. It partners with studios and archives to ensure that everything from classic foreign films (like "The Red Shoes") to Marilyn Monroe's final performance in "The Misfits" once again look like they did when they were first shot.

"Before and after restoration" scenes from "The Red Shoes":

The foundation was started by Scorsese in 1990 with a little help from his friends: Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, Stanley Kubrick and George Lucas. Like the plot of many a Tinseltown thriller, Scorsese and his fellow directors realized the threat to the film industry was coming from inside the house – it was film itself. The earliest stock, nitrate film, was highly flammable and could decompose with age. That's a big reason why up to 75% of all silent films have been lost.

Its successor, acetate film, was safer, but had its own issues. And like many a career in Hollywood, it lacked staying power.

Scorsese said, "By the early 1970s it was decreed that every film had to be made in color. And just at that point in which color because so important, the stock or the negative stock became weaker. And within six years whatever prints we could find were fading. And it just seemed crazy. We have to do everything in color, and now the color doesn't last? It not only doesn't last after 20 years – six years? Come on!"

That same year he fired off an urgent letter to filmmakers saying, "Everything we're doing right now means absolutely nothing." "It was an angry letter," Scorsese said. "It was kind of, I guess, overly enthusiastic. But I wanted to get the attention."

"You were basically putting folks on notice: 'We've got a problem here'?" asked Tracy.

"Yeah, we got a real problem here, and what we should do is force them to deal with this."

Scorsese led a campaign to convince Eastman Kodak to develop a more stable film stock, and then focused on the studios, worried Hollywood's history was vanishing. "The most important thing was being overlooked, and those were the films in their vaults," he said.

Saving those films "wasn't necessarily the biggest priority," said Andrea Kalas, who now oversees the archive at Paramount Pictures (CBS' sister company). In the early 1980s Scorsese presented the major studios with detailed lists of the films they should preserve.

"His encyclopedic knowledge of film is literally unparalleled," Kalas said. "It was amazing that he was able to do that, right, to just sit down with the incredible output of every studio, and just go, 'Yep. Nope. Yep. No. Yep. No.' It's an important list. And it's one that's shared with us; it helps guide our preservation program, among other things."

Kalas was brought on to expand Paramount's preservation effort. They've now restored more than 1,500 films, stored at 28 degrees in a state-of-the-art vault.

These films are the source material for each new technology that's come along, from DVDs to 4K streaming. Even movies you might not consider that old, such as 1986's "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," already need some work.

Paramount recently partnered with the Film Foundation to present some of the restored films from their library. Kalas says the foundation has been essential in making sure Hollywood preserves its film past. "We always have before-and-afters in restorations," she said. "You know, it looked like crap, and now it looks great. Same thing with film preservation. Before the Film Foundation and after is really dramatic."

The Film Foundation also works with institutions like the film archive at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the folks that hand out the Oscars. "The Academy wanted to put its skin into the game to be a part of that movement, to start taking care of films in need of restoration," said Mike Pogorzelski, director of the archive. He says film preservation is not just about caring for Oscar-winners, but lesser-known films, too, including the 1943 film "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp," a Technicolor marvel (and Scorsese favorite).

Restoring it was a labor of love. "Extremely complicated, because of the fact there was actually mold spores growing on the film itself – an absolutely monumental task that no archive could have taken on by itself without the Film Foundation's support," Pogorzelski said.

One of the academy archive's longest-running projects was a digital restoration, with the Criterion Channel, of acclaimed Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray's "Apu" Trilogy. Its negatives were severely damaged in a nitrate fire. "The preservation effort moved from taking care of these deteriorating originals to suddenly scouring the world looking for any surviving film elements, so that they could basically be pieced together almost like a jigsaw puzzle," Pogorzelski said. "In a lot of ways, the 'Apu' Trilogy looks better in the 2000s than it did in the 1950s when the films were brand-new."

Tracy asked, "What is it like when you sit in a screening room and you see one of these fully restored?"

"It is an amazing experience," Pogorzelski replied. "Being able to carry movies like this into the future is one of the greatest and most meaningful parts of what we do here."

And Martin Scorsese, who has been called the patron saint of film preservation, is likely to be remembered not only for the films he's made, but also for the many he's helped save.

Tracy asked him, "How important is this part of your legacy to you?"

"I always thought it was more important," Scorsese replied. "I guess I was more of a teacher than a filmmaker. I particularly enjoy younger people seeing these films. And whether their reaction is, 'I reject it completely, I hate it,' or they become inspired and make some beautiful works of art that enrich the lives of the whole world, this is what we're here for, to enrich each other's lives through art."

‘Film, the Living Record of Our Memory’ Review: How to Save the Movies

Nicolas Rapold

This documentary walks through the delicate task of saving the history of movies with the help of enchanting clips and eagle-eyed preservationists

A canard of the internet age is that more movies are accessible than ever, but “Film, the Living Record of Our Memory” reminds us that our cultural heritage is ever-vanishing and requires constant care just to survive. In this multifarious introduction to motion picture preservation, a crowd of devoted professionals in the field hold up film as not just a vital art form but an essential record of humanity.

Film history is scarred with moments when nobody was minding the store, and when many in the industry were actively burning the store down. Preservationists from across the globe — including rarely represented African, Asian and Latin American archives — here walk through the delicate process of preservation. Obstacles range from epochal shifts (the dumping of silents, the worship of digital), hostile governments (the neglect of Cinemateca Brasileira that led to a fire), and the weather (humidity kills!). Images of rotting reels keep recurring in the film, like a haunting vision.

The film’s director, Inés Toharia, illustrates feats of preservation with lovely clips from obscurities and classics (like “Lawrence of Arabia,” whose sprawling prints were divvied into quarters for restoration by different work groups). Ken Loach, Wim Wenders, Jonas Mekas and Ridley Scott testify, and Martin Scorsese, mastermind of the Film Foundation, is confirmed to be a prince.

Restored by HFPA: "Topkapi" (1964)

Meher Tatna

The poster has a glamorous blonde woman smiling over her bare shoulder, and the caption reads:

“It’s for tonight, darling, in Istanbul . . .

We’ve got a leather vest, a surgeon’s lamp, a suction cup and a Boy Scout knot

Also a mastermind, an electronics genius – and a schmo

Come on – you’re cut in on the theft of the century!”

The film is 1964’s Topkapi, the blonde is Melina Mercouri, the mastermind is her old lover Maximilian Schell, the electronics genius is Peter Morley and the schmo is Peter Ustinov who would win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance, beating out John Gielgud in Becket and Stanley Holloway in My Fair Lady.

In the story, jewel thief Elizabeth Lipp (Mercouri) tracks down her ex-lover Walter Harper (Schell) and entices him into helping her steal the Sultan’s emerald dagger from Istanbul’s Topkapi Museum. The pair decide to hire an amateur crew with no police record as accomplices, and Lipp works her wiles to enlist them. Cedric Page (Morley) is an eccentric British inventor with a sharp wit and a workshop full of dazzling toys, one of which becomes a pivotal prop. Giulio (Gilles Segal, the “human fly”) is a mute athlete who will actually execute the daring robbery. Hans Fischer (Jess Hahn) is a strongman who has to bow out of the caper due to an unfortunate accident, and Arthur Simpson (Ustinov) is the clueless petty hustler they hire to drive a car loaded with weapons over the border into Istanbul.

Arthur manages to get himself caught with the arms at the border by Turkish police, who think he is part of a terrorist gang bent on assassinating foreign dignitaries at an upcoming event. He manages to save himself by promising to spy on his employers, a bargain that is struck when the cops realize the bumbling guy knows nothing. As in all heist movies, nothing goes smoothly. When Hans is injured in a fight, Arthur is recruited to take his place, after he is told of the plan, but also after he has been leaving messages for the Turkish police telling them his colleagues are Russian spies.

The last 40 minutes of the film, when the heist actually takes place, are quite breathtaking, with Walter, Giulio and Arthur scrambling over rooftops to access the museum’s Treasury and trying to cope with Arthur’s fear of heights; Giulio being lowered through a sky window, tethered to a rope controlled by the sweating Arthur, in order to access the dagger; Giulio’s acrobatics suspended on the rope to prevent himself from touching the floor that is wired with alarms; and Elizabeth and Cedric’s ruse to distract a lighthouse man and change the timing of the searchlight that falls on the Treasury’s wall.

Topkapi (1964)

In 1996’s Mission Impossible, director Brian de Palma pay homage to the sequence with a similar scene starring Tom Cruise.

Based on Eric Ambler’s novel “The Light of Day,” Topkapi is directed by Jules Dassin, who moved to Europe when he was blacklisted in the McCarthy witch hunts after being named as a Communist by fellow director Edward Dmytryk. Dassin would marry Mercouri two years after the film’s release: they stayed together until her death in 1994. Mercouri had already starred in several of Dassin’s previous films, including the heist film Rififi in 1955 and the comedy Never on Sunday in 1960. They would work together on eight films. Topkapi was Dassin’s first color film.

The film diverges from the Ambler novel in several ways. The novel’s POV is from the character of Arthur Simpson, and because of that, the reader is unaware of the heist until Simpson learns of it halfway through the story. In the movie, the Mercouri character (whose role is much bigger than that in the novel) informs the audience of the robbery even before the opening credits begin. While Ambler had a hand in the screenplay, sole credit onscreen is given to Monja Danischewsky.

Peter Sellers was originally cast as Simpson, but Ustinov replaced him when Sellers withdrew because, as one account says, he did not get along with Schell. In an ironic twist, Sellers had replaced Ustinov in 1963’s The Pink Panther.

Orson Welles was offered the part of Cedric Page but passed on it. Christopher Plummer and Richard Widmark were in the running for the Walter Harper role. Director Dassin’s son Joseph has a small part as a traveling fair manager who is enlisted to smuggle the dagger out of Istanbul. The younger Dassin would go on to have a stellar career as a singer-songwriter in Europe.

Most of the film was shot in Istanbul, showcasing exotic landmarks like the Topkapi Palace, St. Sophia’s Mosque and the Dolmabahce Palace. Another location was the Kavala harbor in Greece. Interiors were shot at the Boulogne Billancourt Studios in Paris.

For some reason, only the below-the-line crew is listed in the opening credits. The actors’ names appear at the end of the film as they are shown cavorting in an unknown snow-bound location under the caption, “There they go again!” This scene is probably setting up a sequel that ultimately wasn’t to be. There is also a suggestion for another heist in the penultimate scene of the movie. In 1965, a Los Angeles Times article had said Dassin planned a sequel called The Crown Jewels using the same cast, but it was never made.

The film premiered in Paris on September 4, 1964, opening in the US two weeks later. It made $7 million at the box office and was considered a big success. In his New York Times review, critic Bosley Crowther said, “It is another adroitly plotted crime film, played this time for guffaws, and if you don’t split something, either laughing or squirming in suspense, we'll be surprised. We’ll also be surprised if you’re not dazzled by the extravagantly colorful decor and the brilliantly atmospheric setting, which happens to be Istanbul.”

A few years ago, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association asked director Christopher Nolan to choose a film for restoration. His choice was Topkapi, long one of his favorites.

Topkapi was restored at FotoKem Laboratory from the 35mm original camera negative and a 35mm color interpositive. Audio restoration was completed at Audio Mechanics from a 35mm track negative. The photochemical restoration was done by The Film Foundation in collaboration with Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios Inc. Nolan was actively involved in the process. The funding was provided by the HFPA.

Topkapi had its world restoration premiere at the 2022 TCM Classic Film Festival in Hollywood.

Why Do Some Films Get Restored and Others Languish? A MoMA Series Holds Clues

Ben Kenigsberg

History, finances and practical concerns all played a role in preserving the movies being shown at To Save and Project.

A frothy musical comedy from Weimar Germany, starring an actress whose unexpected death at 31 may have been a Gestapo murder. The first known Irish feature to be directed by a woman. An American drama from 1939 distributed to largely Black audiences, starring Louise Beavers as the progressive warden of a reform school.

All these films might have disappeared forever, at least in their complete forms. But all are showing beginning Thursday in To Save and Project, the Museum of Modern Art’s annual series highlighting recent preservation work. Some titles, like the opening-night selection, “The Cat and the Canary,” a popular silent from 1927, were preserved by MoMA itself. Others have been flown in from archives around the globe.

Decisions about which films become candidates for preservation — or even what preservation means for any given movie — are rarely clear-cut. They depend on a combination of commercial interests, historical judgments, economic considerations and the availability and condition of film materials.

Mike Mashon, the head of the moving image section at the Library of Congress, said that when he started at the institution in 1998, there was a common understanding of what preservation meant: making a new film element. That is, a new film copy that could screen in theaters or even a new negative for storage. “The Letter” (1929), an early sound film adapted from a play by W. Somerset Maugham and starring Jeanne Eagels, will screen in the series in a freshly struck 35-millimeter print.

Mashon said there were several reasons for choosing “The Letter” as a project. The library held good original materials, and he expects the film to play well with audiences. “There are plenty of people who really think it’s superior to the Bette Davis 1940 version, and Jeanne Eagels is this great tragic figure in film history,” he said. She died shortly after the picture’s release, and MoMA describes “The Letter” as her only surviving sound movie.

“I Married a Witch” (1942), starring a very funny Veronica Lake as a resurrected witch who first tempts, then falls for, the gubernatorial candidate whose ancestor had her burned at the stake, is even more of a potential crowd-pleaser. Digital technology made it possible to preserve; the restoration was pieced together from several sources that each had its own challenges. The process would have been almost impossible photochemically, said Heather Linville, the supervisor at the Library of Congress’s film preservation laboratory.

Both “The Letter” and “I Married a Witch” received grants from the Film Foundation, the organization started by Martin Scorsese in 1990 to promote the preservation, restoration and exhibition of film. The foundation had a hand in six films showing at To Save and Project, including Luis Buñuel’s “Él” and “The Circus Tent,” a 1978 Indian film that is part of the foundation’s World Cinema Project, whose goal is to preserve movies from countries that have gone underrepresented in film histories.

The foundation’s board members — all filmmakers, including Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Spike Lee and Sofia Coppola — ultimately decide what gets financing, but recommendations are made by archival institutions like the Library of Congress and MoMA, which work with the foundation throughout the year.

She noted that the organizations funding restorations do not have rights to the films. The Film Foundation tries to focus on titles owned by “either individuals or small companies that don’t have the resources to launch a restoration or aren’t paying attention to that because they’re just trying to survive.”

Sometimes repair work is undertaken because the rights holder is interested in a film’s commercial prospects. That was the case with the 1953 science fiction film “Invaders From Mars,” said Scott MacQueen, who supervised the restoration showing at MoMA, and who was until his retirement in 2021 the head of restoration at the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Moviegoers who attend the MoMA screenings of “Invaders” will notice a much different color palette from that on Tubi, which is showing a version that makes the walls of a police station look violet. That was because of a flaw in the original Super Cinecolor process, MacQueen said, and this update comes closer to the intention of the director, the production designer William Cameron Menzies.

Other times not only are the commercial prospects marginal, but the film itself was barely saved from oblivion. Until now, one of rarest titles in the series would have been “Reform School” (1939), restored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In the film, an advocate (played by Louise Beavers, a star of the 1934 “Imitation of Life”) for more humane treatment of incarcerated boys takes over for a disciplinarian warden and establishes a philosophy of trust, with the hope of preparing the boys to re-enter society and be employed.

While the movie was restored as part of Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, an exhibition at the Academy Museum, it had been in the academy’s archive since the late 1990s, when Giancarlo Esposito and Laurence Fishburne donated a collection of films distributed by Ted Toddy, a white producer who put out titles with Black casts aimed at Black audiences.

Josef Lindner, the preservation officer at the academy, said it was not clear that there were any surviving film copies of “Reform School” other than the academy’s 16-millimeter print. Still, whether it merited restoration was, for a time, a vexed proposition. Some of Toddy’s movies had a problematic reputation. Many, though not “Reform School,” featured Mantan Moreland, an actor known for broad, minstrel-like caricatures.

Curators helping to plan the “Regeneration” series a few years ago provided the impetus. Seen today, “Reform School” seems ahead of its time in at least some respects, particularly in its depiction of a female warden.

Collaboration among archives is often the key to rediscovery. “Private Secretary,” a 1931 musical comedy from Germany, did not survive in any known, complete 35-millimeter copies. But Stefan Drössler, the head of the Munich Filmmuseum, was able to view a 16-millimeter print at the Library of Congress, which had acquired large quantities of German films after World War II. Two 16-millimeter prints from the library and three reels of a 35-millimeter print form the basis of the new restoration.

“Private Secretary” stars Renate Müller, whose death in 1937 has never been firmly resolved. It may have been a suicide or a murder by the Nazis. (Some sources suggest that Hitler was interested in her, but Drössler said that Müller “loved Georg Deutsch, a Jew who had to emigrate and whom she visited as often as possible.”) She plays a bank typist who does not realize that the man she has fallen for is the bank’s director.

National archives generally have a mission of preserving their countries’ cinematic heritage. But Ireland came to the task late: The country did not have a film repository or a history of preservation until the late 1980s and early ’90s, said Kasandra O’Connell, the head of the IFI Irish Film Archive.

This year, the archive will bring to MoMA a digital restoration of “This Other Eden” (1959), a drama made in the early years of Ardmore Studios, the only studio in Ireland at the time, O’Connell said. The film is also of historic interest in how it dramatizes British-Irish tensions and the legacy of a figure modeled on the Irish revolutionary Michael Collins.

“It’s the first Irish feature we know of that was directed by a woman — even though she was British — Muriel Box,” O’Connell said.

Britain, in a way, saved the film. “We didn’t have our own laboratories in Ireland, so all of the material had to go to the U.K. to be processed,” O’Connell said. Because of that, a lot of negatives ended up in British archives. “If they hadn’t, they probably wouldn’t exist,” she added.

For the Thai Film Archive, MoMA’s showings of “The Adulterer” (1972), a languid thriller about a hermit fisherman, a woman who washes ashore and a man from her past, are a chance to introduce a classic of Thai cinema to New York audiences. Chalida Uabumrungjit, director of the archive, said the filmmaker, Somboonsuk Niyomsiri (directing under the pseudonym Piak Poster), is relatively unknown even to audiences in Thailand, even though the film is on the country’s equivalent of the National Film Registry.

She also noted that the Thai archive sometimes provides support for neighboring countries, like Myanmar, that do not have archives of their own.

Lindner, from the Academy, summed up one of the problems of preservation a different way. “There are so many films that are lost that we know are lost,” he said. “But then there’s the things that we don’t even know that we should be looking for.”

To Save and Project runs Jan. 12 through Feb. 2 at the Museum of Modern Art. Go to moma.org for more information.